10

11

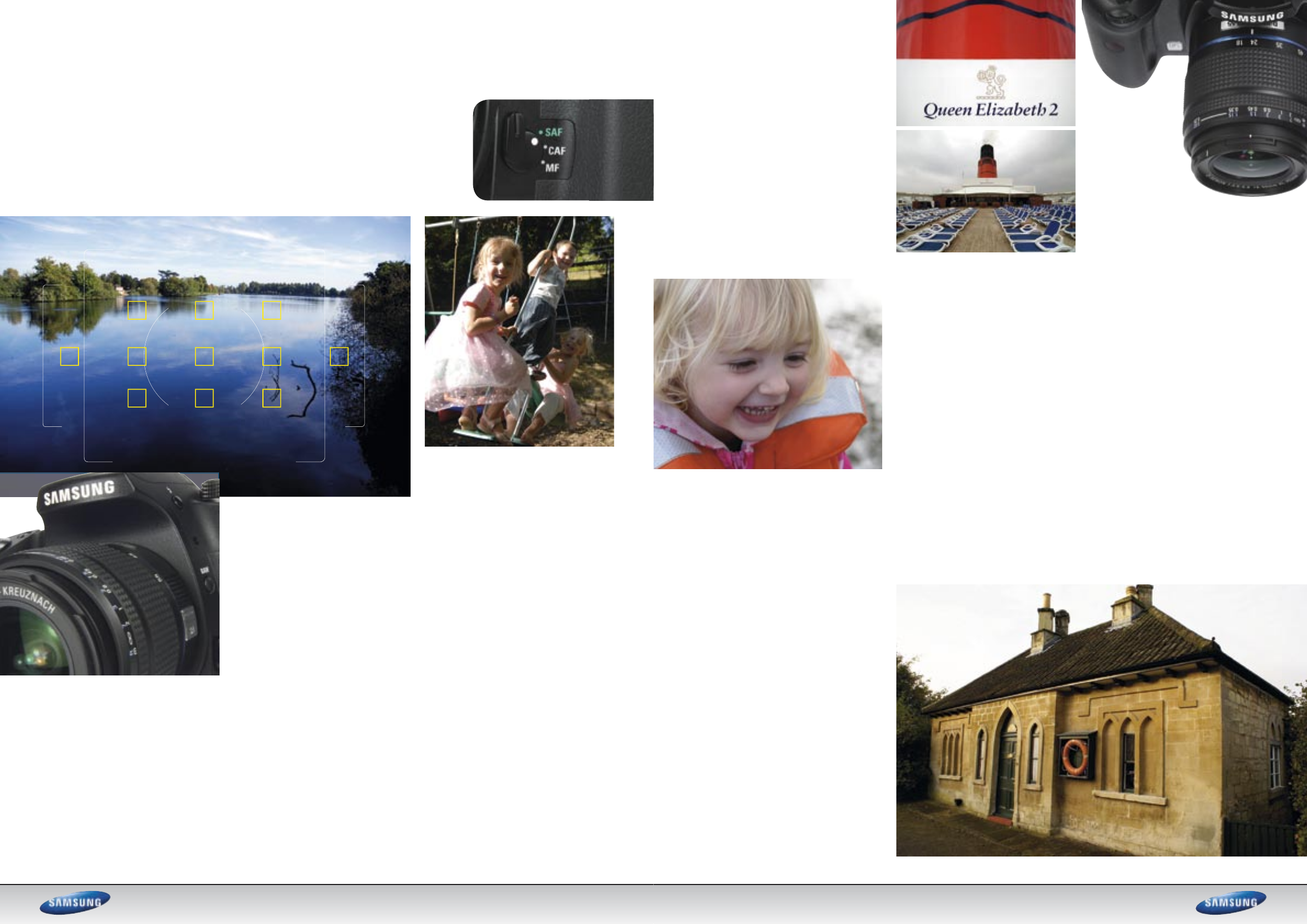

WIDEANGLE

TELEPHOTO

LENSES: FOCAL LENGTH

AND FOCUS MODES

No matter what digital SLR you own, there will be a range of lenses available

for it that will be able to cater to almost any subject, from close-up or macro

work, wideangle shooting to telephoto shots. It will also have a range of

focusing options and controls at your disposal

Focus and

focus control

A DSLR will have inside it a system to

measure the distance from the plane the

sensor sits on inside the camera to the

subject you’re trying to shoot. Usually a

combination of mechanisms in the camera,

it will include some or all of the following,

usually working in conjunction. There will be

a range-fi nding device, an infrared beam

(or several), colour and focal length

information and a phase difference or

contrast detection system. The information

gathered by these systems is combined with

one aim: to focus light onto the sensor (the

focal plane) to ensure you get a sharp image.

The viewfi nder

and focus control

When you look through a DSLR viewfi nder

you’ll see a series of autofocus (AF) points

that will usually illuminate for a moment in

red when the focus is achieved, head-up

display fashion. Some DSLRs have three

such points, some can have over 30 grouped

around the viewfi nder, but all are used to

indicate that focus is achieved and in which

part of the scene.

The reason there are multiple AF points

is to make focusing more accurate for

off-centre subjects, or for subjects that are

more complex where an array of focus points

might be employed to get a best overall

focus position, ensuring all the elements

selected are sharp. Using the camera

controls, you’ll be able to override these

systems if you wish, selecting separate

or groups of AF points to help further tailor

the focus position for the subject. In practice,

the type of subject will determine the focus

points that you wish to use. In a portrait,

where focus on the eyes is important, you

may defi ne a single AF point. For a large

building with architectural projections, a

group of AF points might work best to keep

everything in the fi nder sharply rendered.

Focus modes and

when to use them

You will also have various focus modes

to play with, each providing advantages.

The two main focus modes are Single AF

and Continuous AF. As their names suggest,

the former will lock onto a subject and remain

fi xed there until after the shot is made, even

if you or the subject move, making it best for

static subjects. The latter provides a focus

system that continually looks for a subject

once it’s locked onto it and changes the

focus position if it (or you) move, always

keeping it sharply focused.

Another type of AF system, Predictive

AF, is similar to Continuous in that the focus

can track a subject, but this mode does not

lock onto it until the shutter is fi red. The AF

actively monitors the position of the subject

right up until the shutter exposes light onto

the sensor. It predicts the subject’s position in

the frame at the point it will be when the

shutter starts to move and focuses there.

With Predictive AF, it is quite possible the

subject does not look sharp in the fi nder

at any point until the shutter fi res, so it can

take some getting used to.

Finally, there is Zonal AF (what Canon calls

A-DEP or ‘automatic depth of fi eld control’),

which is ideal for keeping larger or more

complex subjects in focus where the depth

of fi eld is critical to keep a zone of the scene

sharp. It is achieved by the camera checking

all the active AF points, and then calculating

the shutter speed and aperture required to

keep all in focus, making it fast and simple

to use because you don’t have to worry

about adjusting apertures and checking

depth of fi eld yourself.

Lens focal length

Focal length is the name for the distance

between the fi lm plane and the focal point

(or the optical centre of the lens) when the

lens is focused at infi nity and expressed in

millimetres and shown on the lens. In plain

speak it is the name given to an indication

of the angle of view of a particular lens,

where a shorter focal length lens – such

as a 28mm lens – will provide a wider angle

of view than a longer one – such as 100mm.

It stands to reason therefore that you

can fi t more of a scene into a shot using a

wideangle lens than that from a telephoto

lens, which is why you use longer lenses

to get ‘closer’ or get greater magnifi cation

of a scene. A wideangle lens is ideal for

landscape work or for shots where you will

need a lot more room to fi t everything in.

Telephoto lenses are ideal for getting close

in wildlife photography, for example.

Zoom lenses

and fi eld of view

Zoom lenses have a range of focal lengths

built into one optical device enabling you

to carry one lens that offers a broad range

of uses and fl exibility – the reason they are

so popular in fact. However, zooms are

often not as good optically as a prime lens

(lenses with one focal length) because they

are an optical Jack-of-all-focal lengths, rather

than master of one.

Depending on the camera you own, you

may have a fi eld of view multiplier to add to

the focal length of your lens. This is because

the lens has its focal length shown in relation

to 35mm fi lm frame size and your camera

uses a sensor smaller than a 35mm frame

of fi lm (unless, that is, the camera you are

using is a full frame – 35mm-sized – DSLR,

in which case the focal length shown on

the lens is the correct one).

Typical fi eld of view multipliers are 1.5x

(or 1.6x) and 2.0x. In the former group, a

lens with a 50mm focal length will become

a 75mm focal length lens (this includes

APS-C sized sensors such as those in the

Nikon D40). In the latter group (cameras

using the FourThirds format eg. Olympus’s

E-400) it will be a 100mm focal length.

Lenses and

aperture control

Lenses use a controllable aperture, analogous

to the pupil in a human eye, altered to vary the

amount of light entering a lens and reaching

the sensor. Aperture control also affects the

depth of fi eld, with larger apertures (smaller

F numbers such as F/2.8) providing a

shallower depth of focus than smaller

apertures (larger F numbers, such as F16).

The technical side of why this happens

is that a smaller aperture will straighten light

more (even non-focused light rays) through the

smaller aperture on its path to the focal plane

(the sensor) than larger apertures. The closer

the light is to a point at the focal plane the

more ‘in focus’ it will be. Conversely, a wide

aperture allows non-focused light to enter

more diffusely, thus appearing more blurred.

A zoom lens with a fi xed maximum aperture

throughout its range (typically around F/2.8)

is expensive, yes, but provides some real

advantages in that you can get more creative

control of depth of fi eld at any given focal

length. A zoom lens whose aperture reduces

as the focal length increases (a variable

maximum aperture lens) is less fl exible since

you have a reduced maximum aperture to play

with, thus reducing control of depth of fi eld

and the amount of light entering the lens.

Therefore a wide maximum aperture lens,

zoom or otherwise, offers advantages over

variable aperture lenses, both in terms of

the amount of light entering the lens (and

so shutter speeds at your disposal) but the

amount of control over depth of fi eld at a given

focal length (in zooms), making them far more

fl exible. Typically, they are much better

optically speaking as well.

Perspective

and depth of fi eld

Differences in focal length can alter what you

see in an image. A wideangle lens will render

all elements smaller in the frame (unless the

subject is very close to the lens) and can

distort perspective, as the optics used ‘bend’

light to fi t it all into and onto a camera’s

sensor. It is for this reason optical distortions

can appear in an image such as barrel

distortion, which gives the appearance of

curling the image corners down and round

at the top and vice versa at the bottom.

Another wideangle lens consideration

is the way perspective distorts if the camera/

lens is tilted backwards; say when shooting

a tall building. This will make the verticals

appear to converge towards the top of the

shot. While this can be used to your

advantage sometimes, or corrected in

software, the easier alternative is to keep

the camera perpendicular to the subject

or use a (rather expensive) tilt-and-shift lens

designed to help correct for such problems.

Telephoto lenses get you closer with a

smaller fi eld of view and in so doing they

foreshorten perspective, appearing to bunch

everything closer together in the frame. They

also reduce depth of fi eld – the amount of the

scene in front of, and behind the main subject,

that is sharp. Again, this can be used to great

advantage if there are distracting back-

grounds. It is also why portrait lenses typically

have focal lengths of about 90mm to 135mm

to both give the most fl attering perspective to

a face and help reduce depth of fi eld.