depth-of-field. By the same token, a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 will be eas-

ier to autofocus (or manually focus) than one of the same focal length with an f/4 max-

imum aperture, because the f/4 lens has more depth-of-field and a dimmer view. That’s

why lenses with a maximum aperture smaller than f/5.6 can give your D7000’s auto-

focus system fits.

To make things even more complicated, many subjects aren’t polite enough to remain

still. They move around in the frame, so that even if the D7000 is sharply focused on

your main subject, it may change position and require refocusing. An intervening sub-

ject may pop into the frame and pass between you and the subject you meant to pho-

tograph. You (or the D7000) have to decide whether to lock focus on this new subject,

or remain focused on the original subject. Finally, there are some kinds of subjects that

are difficult to bring into sharp focus because they lack enough contrast to allow the

D7000’s AF system (or our eyes) to lock in. Blank walls, a clear blue sky, or other sub-

ject matter may make focusing difficult.

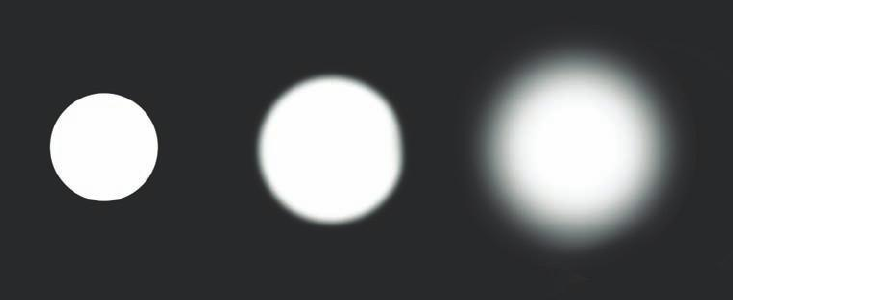

If you find all these focus factors confusing, you’re on the right track. Focus is, in fact,

measured using something called a circle of confusion. An ideal image consists of zil-

lions of tiny little points, which, like all points, theoretically have no height or width.

There is perfect contrast between the point and its surroundings. You can think of each

point as a pinpoint of light in a darkened room. When a given point is out of focus,

its edges decrease in contrast and it changes from a perfect point to a tiny disc with

blurry edges (remember, blur is the lack of contrast between boundaries in an image).

(See Figure 5.8.)

If this blurry disc—the circle of confusion—is small enough, our eye still perceives it as

a point. It’s only when the disc grows large enough that we can see it as a blur rather

than a sharp point that a given point is viewed as out of focus. You can see, then, that

enlarging an image, either by displaying it larger on your computer monitor or by mak-

ing a large print, also enlarges the size of each circle of confusion. Moving closer to the

image does the same thing. So, parts of an image that may look perfectly sharp in a

David Busch’s Nikon D7000 Guide to Digital SLR Photography140

Figure 5.8

When a pin-

point of light

(left) goes out

of focus, its

blurry edges

form a circle of

confusion (cen-

ter and right).